View the full Article on:

Addimmune

Author: Addimmune Staff

Are some people resistant to HIV?

Under normal circumstances, exposure to HIV leads to infection, which inevitably leads to AIDS after years of immune destruction by the virus. However, there are certain groups of people that deviate from the norm:

- Non-progressors: People who are infected with HIV, but do not progress to more advanced stages of infection. Also called long-term non-progressors (LTNPs)

- Elite controllers: People living with HIV who are able to maintain undetectable viral loads for at least 12 months despite not starting antiretroviral therapy (ART).

- HIV-resistant: People who have had repeated exposure to HIV but do not become infected.

- Viraemic controllers: People who are able to maintain a low but detectable viral load off ART with CD4 counts above 200.

- Post-treatment controllers: People who are able to maintain undetectable viral loads even after discontinuing their ART regimen (post treatment)

A patient can be classified as part of multiple groups at the same time, and each of these groups has something to teach us about HIV infection. The individuals in these groups have been studied intensely to glean details on the virus, its interaction with the body, and how that information can be applied to cure research. Before we dive into each of these groups, a quick disclaimer: if you are someone living with HIV, this information is not a substitute for medical advice. Each person is unique, so please consult your doctor before making any changes to your treatment plan. Without further ado, let’s get into it!

Why do some individuals have HIV-resistance?

Once the chain reaction of HIV infection begins, it is almost impossible to stop without medical intervention, which is why studies on HIV resistant people are so fascinating. These populations demonstrate a resistance to the very beginning stages of HIV infection. Studies in these populations seem to show that certain genetic variations allow people who have been exposed to HIV to avoid becoming infected by the virus. Simplifying the work of Poudrier et al, the genes that control how the immune system recognizes pathogens, how the immune cells interact with their environment, and most famously, the gene that makes Helper T cells susceptible to HIV, CCR5, are all implicated in the risk of infection from an exposure to HIV.

In the cases where HIV has been declared cured, patients whose immune system was destroyed to kill cancerous immune cells were given new precursor cells to the immune system which lacked CCR5. These cases demonstrate that under certain circumstances, an immune system that can resist HIV infection has the potential to kill and clear the virus. This has led research groups like Addimmune to develop genetic medicine which could provide a similar benefit to people living with HIV without necessitating the dangerous task of wiping out and replacing the entire immune system.

Overall, studying HIV resistance and applying that knowledge toward next-generation therapeutics is a promising area of research which we hope will provide the missing cure to an epidemic which has raged for over 4 decades.

Non-progressors

At the beginning of the HIV epidemic, before any effective medications were available, scientists and doctors observed a small population of people living with HIV did not progress to Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) or death. These people were able to maintain normal Helper T cell counts in the blood for many years without medication, sometimes for over two decades. While some of these non-progressors were shown to be infected with strains of HIV which were not as pathogenic, many others were shown to have an immunologic advantage over HIV which wasn’t directly attributable to viral strain.

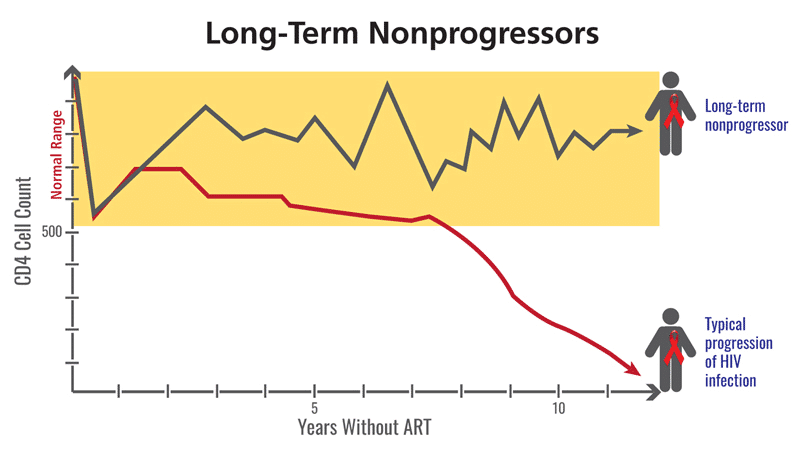

A defining feature of AIDS is the lack of sufficient numbers of Helper T cells, also known as CD4 positive (CD4+) T cells. Gaarbdo et al help contextualize what a non-progressor is:

“The CD4+ cell count in a given patient at any time is the result of production, destruction, and traffic between blood and lymphatic tissue, and when the destruction exceeds the production the CD4+ cell count decreases. Thus, LTNP and controllers may have differences in production, destruction, or distribution of CD4+ cells compared to progressors in order to maintain a normal CD4+ cell count.“

Figure 1: The progression to AIDS tracks with the decrease in CD4+ T cells, and while NPs and LTNPs are infected with HIV, their immune system does not degrade in the same way as a progressor. Photo credit: clinicalinfo.hiv.gov

The terms “non-progressor” or “long-term non-progressor” refer to distinct groups of people who do not experience increased disease severity and maintain a healthy CD4 count over a long period of time, despite the lack of antiretroviral therapy. They are still infected with HIV, and may even have detectable viral loads, but for some reason, they do not succumb to disease progression despite the presence of HIV. These patients have been studied since the very beginning of the HIV epidemic in pursuit of a deeper knowledge of HIV pathology.

Viraemic controllers and elite controllers

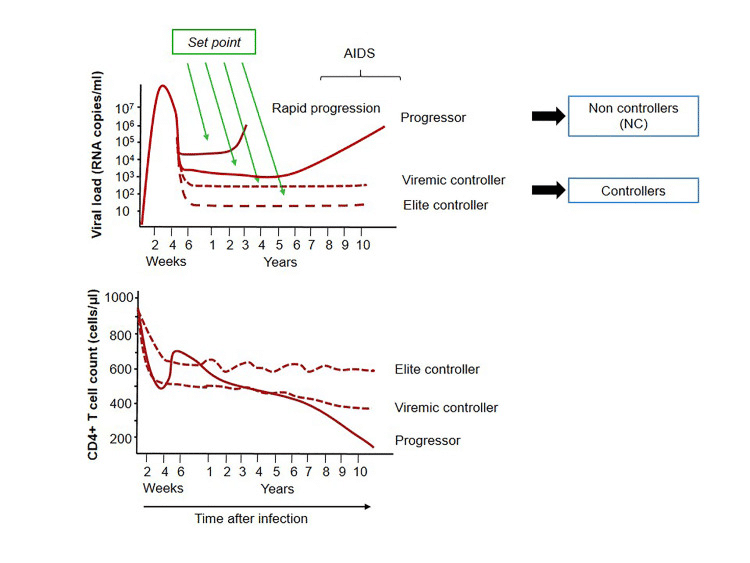

The interactions that HIV has with the immune system are at the center of the pathogenicity of HIV. Analyzing the preserved immune function of non-progressors provides a patient-centric view of disease progression, and to form a more complete understanding of infection, we can also look at the infection from a virus-centric viewpoint. This is where viraemic and elite controllers come in. These populations are defined as:

- Elite controller: Elite controllers (ECs) are people living with HIV who have viral loads below the limit of detection of commercial tests (<50 viral copies per mL) even when they are not taking ART, which is where the term “undetectable” comes from. Under the U=U guideline, it is accepted that undetectable is equivalent to untransmittable.

- Viraemic controller: Viraemic controllers (VCs) are able to control HIV RNA to levels between 200 and 1000 viral copies per mL without ART. These levels are high enough to register on commercial viral load tests, but the patients are able to maintain elevated levels of helper T cells and are not actively progressing to advanced stages of infection.

These patient populations usually lose control of HIV eventually, and they eventually need to begin taking medication. AIDSMap provides more context on ECs:

“The term doesn’t describe a permanent state; elite controllers frequently go on to develop detectable virus in the blood, as well as other HIV-related complications. In one study, the median time to disease progression for elite controllers was four years. In other words, if there were 100 elite controllers, by four years, 50 of them would either have a detectable viral load, falling CD4+ count or an AIDS-defining illness.“

Using ultra-sensitive research grade tests instead of standard commercial tests, the majority of elite controllers show the presence of HIV RNA in the blood. Measuring HIV RNA shows the number of virus particles in the blood while measuring the levels of HIV DNA shows the number of HIV-infected cells in the blood. This indicates that HIV is actively replicating in these individuals, but at such a low rate that it’s incredibly difficult to find. With this understanding it is easier to understand why HIV, a highly mutation-prone virus, is able to eventually find a way to replicate heavily and cause a progression to AIDS.

Figure 2: The top graph shows the viral load of progressor and controller subgroups over time, while the bottom graph shows the trend for CD4 count. Photo credit: Elena Gonzalo-Gil, Uchenna Ikediobi, and Richard E. Sutton

The levels of HIV replication coupled alongside its mutation rate are important concepts in HIV science. The lower the levels of HIV replication, the fewer chances the virus has to create mutant strains which resist medication, or evade existing immune responses. To avoid these complications and prevent disease progression, minimizing viral load is the goal of treatment plans. As such, doctors maintain a watchful eye on their patient’s HIV RNA levels to make sure that if viral load increases, they can be ready to respond with a combined antiretroviral therapy regimen.

Post-treatment controllers

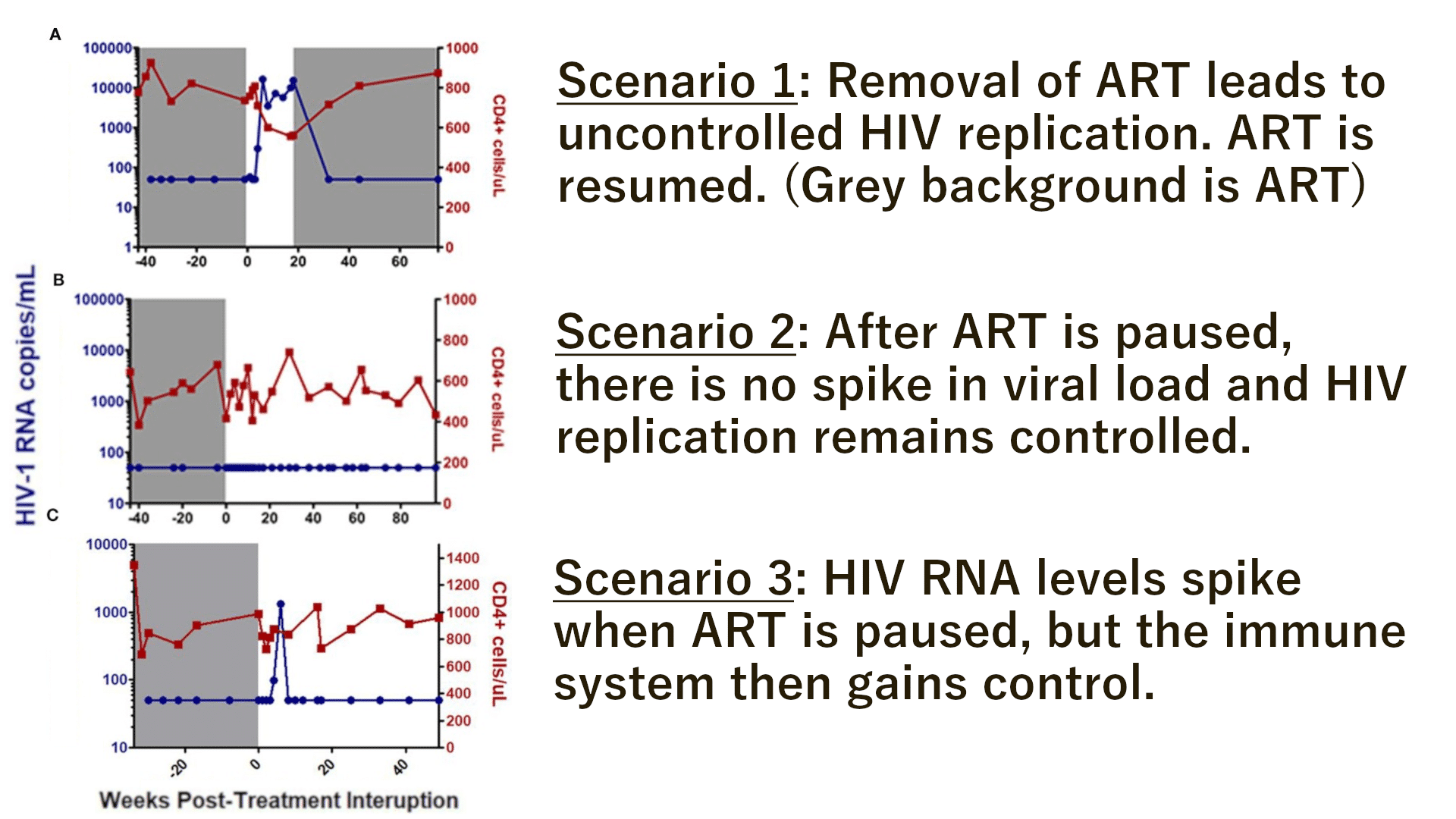

Some people living with HIV will coordinate with their doctor to take a break from their medication, and in rare instances, these patients can maintain undetectable viral loads for long periods of time. These post-treatment controllers (PTCs) offer an intriguing perspective on HIV infection, so the Control of HIV After Antiretroviral Medication Pause (CHAMP) study was initiated to understand more about this phenomenon. With PTCs being defined as people who remained off of ART for over 24 weeks and maintained the viral load of under 400 viral copies/mL of blood for at least two thirds of the time points, a ton of useful data was generated:

- Individuals who initiated ART early in the course of HIV infection were more likely to exhibit viral post-treatment control when discontinuing ART. 13% of early initiators exhibited some sort of post-treatment control compared to only 4% in groups that waited until chronic stages of HIV infection before initiating ART.

- Of the patients who exhibited post-treatment control, 75% maintained virologic suppression through year 1, 55% through year 2, and then 41%, 30%, and 22% through years 3, 4 and 5 respectively.

- When removed from ART, viral load patterns looked different for different patients. Some participants had early spikes in HIV RNA then gained control of their viraemia later while others remained controlled throughout their interruption. Figure 3 shows the three scenarios possible for PTCs.

Figure 3: Overview of the possible scenarios when HIV patients are removed from ART. Adapted from “Learning from the exceptions:HIV Remission in Post-Treatment Controllers” by Etemad et al.

The unique features of each person living with HIV, the particular strain(s) involved, and factors such as the timing of ART initiation change the outcome of treatment interruption. While there are extremely rare cases of PTCs which have maintained viral control for over 10 years, the overwhelming majority of patients do not achieve PTC status, and those that do inevitably lose control of viral replication and return to ART regimens. These cases show us a hopeful perspective in which the natural immune system gains partial control of HIV, but the goal of HIV cure research is to provide an intervention which can induce long lived, durable viral remission.

How to apply this knowledge to HIV cure research

There are people who, despite heavy exposure to HIV, do not seem to be susceptible to HIV infection – these HIV resistant populations are our first clue that HIV is not an unsolvable problem. Of the people who do become infected, non-progressors were the first group of people that scientists could study in hopes of finding ways to exploit HIV’s weaknesses. Unlike other people living with HIV, non-progressors did not lose immune function in the same way as others even despite the lack of available medication at the time. In fact, even after medications became available, there were still some populations that were able to maintain low or undetectable viral loads without ART. Furthermore, some patients can gain control of HIV for long periods of time after stopping ART.

All of these points depict HIV infection as a difficult, but not impossible, problem to solve. Along this line of reasoning, a widely applicable HIV cure should be possible. In today’s age, testing and treatment are widely available, preserving millions of lives, so any HIV cure project would realistically be used on people living with HIV who are currently on ART. There are two theoretical cures for HIV:

- A sterilizing cure, which would eliminate all traces of HIV from the body, including latently infected cells. This type of cure would involve an accurate targeting system that can identify and destroy cells which are infected with HIV.

- A functional cure, which would grant the immune system the power to durably control HIV in the long term without ART. A high level of control which maintains undetectable status, similar to an elite controller, would be ideal. This type of cure would most likely mirror the effects seen in post treatment controllers who also fall into the elite controller category.

It is worth mentioning that these are theoretical cure types and they may not even be very descriptive of the HIV cures that could materialize in the near future. In fact, the only times that HIV has ever been declared cured involved immune cells with genetic resistance to HIV (or more accurately, their progenitors) and the word “cure” was not uttered until scientists felt confident that they could not find any traces of replication-competent HIV in the body. While the genetically modified immune cells would be placed into the “functional cure” bucket, we could also dare to say that the overall result of those case studies represents a “sterilizing cure”.

At Addimmune, we envision a world where HIV is curable using safe, scalable methods. By learning from the decades of research in various populations of people living with HIV, and the instances where HIV has been cured, we have designed a gene therapy that gives immune cells defensive HIV resistance so they can focus on mounting an effective offense.

It’s like installing antivirus software on your computer, except it’s for your immune cells.

It is our hope that these cells will be able to exert a sustained pressure on HIV by directing the immune system’s anti-HIV response to kill infected cells, but that their HIV resistant qualities will allow them to persist without being infected by the virus. Our clinical trials are underway and we’re moving full steam ahead. To learn more about the treatment itself, take a look at this page – and check this page for progress on the clinical trials.